|

Michael Meade (who hosts a wonderful podcast called Mosaic Voices that talks about soulful mythology in our present day) describes the New Year as a rite of passage; a ritual to end the old year, and celebrate the start of a new period. A time of renewal, of beginnings. A threshold time. A liminal space; 2019 is gone, 2020 is yet to come.

Grief is also a threshold time. Grief plunks you in liminal space - betwixt and between two lives that don’t seem to fit; you live suspended between a past for which you long and a future for which you hope, to quote Gerald Sittser, from his book A Grace Disguised. Living in liminal space is hard. It’s uncomfortable. It’s unknowable. In a society that has an abundance of drive to DO things, and become "better" (what does that even mean?), existing in a threshold time can feel like you are doing it "wrong." You aren't. This is precisely what grief calls us to do - slow down, and pause. Give yourself the time to be in emotional and spiritual intensive care. It’s in this threshold space that you figure out how to live your changed life, and that takes time, it takes living, and it's really, really hard. This is how loss and grief become an integrated part of your whole. If you’ve been living moment to moment, or hour to hour to get through the early months after a loss, extending your mind into the future (planning a resolution at New Year’s) can be especially daunting and lonesome. Opens up a new abyss of grief and longing for things to be different. And yet, they aren’t. I remember talking to a dear friend about this - how as time went on, and we started living day to day, then week to week, then month to month, it was harder in different ways. As such, the custom to make a New Year’s resolution can be wrought with anxiety, especially when life has changed so much already. If this resonates with your experience, here are some things to consider:

The Wound of Love by Maya Luna Today I gave up On healing my trauma I gave up On practicing the skills To become whole Today I gave up On evolving Into that ever elusive Better version of myself Today I submitted To the wound of love I stopped pointing at it Looking at it Soothing it Tweaking it Fixing it Finessing it Hiding it Polishing it I stopped this game of separation I crawled inside the wound And spread it open I decided to wear it like a gown I accepted my total and utter Failure To be anything else But me

Blessings to you all.

You're perfect just the way you are... I know it may not feel like it, but know your heart is still shining like the sun. Namaste, Sandy

0 Comments

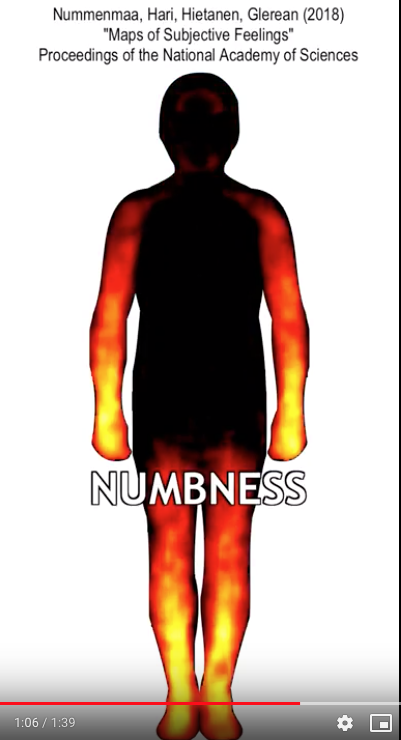

*This post was written the month after the death of my Dad* When a loss happens, it's natural to want to solve it right away. To do something, anything to make it better. But staring a grief support group too early can be counter productive. These early days of grief remind me of something important. Early on, there is a tendency to move away from the reality of the loss. This is a protective response of the heart. I see this in myself. Instead of using yoga as a way to process what I'm feeling, I've been using it as a distraction. I want my practice to be sweaty and muscley and fast...not a lot of time to think or feel. This is what I need right now. It would be counter productive to the needs of my heart and spirit to force exploring emotions that I'm not ready to feel. As time passes (and there is no set timeline), and numbness wears off, you will naturally move towards the pain and realities of the loss. It's often as the numbness fades and the realities of living with loss set in, that more support is needed. It is then, that a class like Yoga for Grief Support may be helpful. In the Yoga for Grief Support program, we use yoga and meditation as a way to "go inside" and explore the pain and reality of the loss. One has to be "ready" to do this. Starting too early may feel like you are driving with one foot on the gas and one foot on the brake. In most cases (not all), it may take a number of weeks to a few months to be ready for a class like Yoga for Grief Support. Each circumstance is different, with a number of factors affecting someone's readiness. Sometimes, people start a group and realize it's too soon. That's OK too - it's impossible to know what this grief experience is like because each loss is so different. If you want to explore this further with me, feel free to reach out via email. I find the poem below, by Wendell Berry to be helpful when considering if you need specific grief support. Sometimes, it is when you don't know what to do, that you are ready to start. It may be that when we no longer know what to do November was a rough month in my world. On November 14th, after a two year illness, my Dad died. He had pulmonary fibrosis. Over the past two years, I have been mentally drafting a blog post called: When It Happens Again. IT being death and emotional trauma. I remember feeling such protest as I was considering the fact that IT could (would) happen again. A deep revolt and fear around knowing what grief is like, and not wanting to go down that path again. This mental blog post I had drafted was going to be a piece around how I would cope with grief the next time 'round, based on everything I had experience and learnt since the first time 'round. Things like:

I never did write that post. I kind of wish that I had - then I could refer back to it as a little pep talk for myself. Now that IT has happened, all the best laid plans I had mentally made, have dissolved into the cocoon of shock. I'm steeped with numbness and shock that has dulled the realities of my outer and inner world. My mind isn't working as quickly. I'm forgetful. I start 16 different tasks in a day and don't complete any of them. I didn't brush my hair or my teeth today and I have nothing to show for how busy I felt. I don't feel the protest the way I thought I would. That must have burned itself out during my dad's illness as I watched him slowly (and then quickly) decline. My anxiety is gone. I was paralyzed before his death about what was going to happen. Now it's happened and I've been relieved of that worry. That lack feels numb too. And yet, the world says speed up when everything within my body and mind says slow down. I feel this tug of war in my gut and my chest and I dread having to navigate it; It takes so much extra energy. I know the numbness and shock serves a purpose. The heart can't feel the full reality of the loss at once. It is not worth forcing myself out of this cocooned place. My wise body/mind/spirit will naturally dose itself with the pain and the reality of the loss, in it's own time. My conscious mind may not be privy to this timeline. So, what do I do? I start right where I am. I rest. I cocoon. Be gentle with myself. I've noticed more intrusive thoughts in the past few days around the circumstances of his death. This too, I know is normal. Instinctual even. There is a natural tendency to go over it all, again and again. Cognitively trying to make sense of it. While *the world* wants me to get on with living, and get back to life, I know that pausing, even going backwards into the past is important grief work. It makes the unreal real, and is an important part of processing the reality of the death. I've found myself gently approaching the pain and reality a couple of nights ago. I drove by the hospital and looked up to the window that was his room. It made my chest ache. I want to live-backwards. I want to spend some time reviewing what-the-hell-just-happened. I'll probably write it out. Get those thoughts out of my head and onto paper. I may even walk from where I would park my car, to the unit he was on, just to remember and feel it when I'm ready to. But, who knows! Grief is unpredictable, and living-in-the-moment for me at this time means responding to whatever need arises, when it does. It's all vital work. Grief work. Mourning work. I do know that this time 'round I am part of (and can rely on) a community of people who "get it" to support me and I feel all those people in my cocoon with me.

This time 'round, I'm more open to receiving care and being cared for. That feels really nice. Thank you. To those near and far, known to me and unknown. The grief warriors that live this every day. We are not alone. Sandy Before and After Loss: A Neurologist's Perspective on Loss, Grief and Our Brain by Lisa M. Shulman, MD"I expected grief to be unbearable sadness, but it wasn't that at all. It was profound instability." (preface, page xi)

The above is the quote that starts this book. I read it. Stopped. Read it again. I can relate to that, I thought.

I actually thought that many times throughout this book - which is what I liked the most. I saw myself in the pages. That, combined with the science she describes, helped me understand my own experience of grief and trauma in a much deeper way. Not only that, this book is a rabbit hole of quotable quotes and excellent references. The bibliography is pages long...a gold mine for a book worm like myself. Anyway... Lisa Shulman is a Neurologist, and this book is a memoir of her own experience with grief before her husband died, and after, as the title indicates. Her personal experience is combined with her knowledge of how the brain works to organize our reality...and in the case of grief, how it it becomes disorganized and damaged after a loss. The neurology of grief.

Before:

Lisa writes about her life with Bill (her husband) when he was sick and dying. The one thing that struck me was how their intimacy with each other was a barrier throughout his illness. "We're stumbling because we care to deeply for each other" (page 6). I found it heartbreaking to look into such an intense and personal time in their life and relationship...but, as Lisa writes later in the book, the trauma and disorientation of loss is based not only in the biology of sorrow, but the biology of intimacy. Our brains are wired a certain way because of our relationships and intimate bonds. Reading about Lisa's life with Bill before his death helps to illustrate this point in the "After" section of the book. After: There is something about how Lisa Shulman writes. It is surprising - she captures perfectly, states, emotions and thoughts that I've had, but a) haven't been able to put into words, or b) hesitant to talk about for fear of...I dunno...judgement maybe? For example, her disdain for condolence cards (I remember feeling this way) and her desire to be more a part of "the other side" with Bill, than the side of the living (yep, I've felt this too). In her words: Condolences: Hundreds were received - all unwelcome. "I'm moved when I sense the grief of others, but i envy how they touch down in my world and return to theirs. Condolences don't begin to fill the canyon of loss" (page 42). After his death: "I continue to live with Bill, in an inner world where, from moment to moment, i’m conscious of his response to the day’s events, to how my life unfolds. He continues to guide me. I was his muse; now he is mine" (page 46). *As I write this, I'm finding it hard to limit myself to just one example of a piece that "hit home" for me...* She captures a lot of the nuances of the grief experience that are irrational, heart centered and spirit based very clearly and wholly. Hence, when Lisa shifts from writing about her personal experience of grief, to one more of science and reflection on the neurology of loss I got tense. I was worried that this beautiful piece of writing was turning cold...rational...cerebral. But, in the end, it didn't at all - she was able to still be both - rational and irrational. Head and heart. Mystical and scientific. She still used her personal experience to illustrate her points, but she refers to many studies, outcomes, and sciencey things, like the neuroplasticity of the brain. The overall effect works. I was fascinated by the science that explains so much of what I experienced personally with grief. Everything from dreams to mindfulness to post-traumatic stress. I've learnt over the years that I don't need proof of anything beyond my own personal experience when it comes to grief, but it really was reassuring to understand some of the biology and neurology behind grief. “[G]rief is a manifestation of neurologic trauma, and is evidence of injury to brain regions that regulate emotions. Grieving is a healthy protective response. It’s an evolutionary adaptation to promote survival in the face of emotional trauma, one where the injury goes undetected since daily function is preserved.” (pg 142)

I found the end of the book very hopeful. She writes extensively on the science of emotional restoration and healing - from meditation to medication. She illustrates how a heightened nervous system post trauma can be tamed by periods of meditation, and warm companionship, where a healthy outcome is self-exploration and growth. She believes in both mindfulness as a way to immerse oneself in witnessing their grief, but also periods of distraction which give much needed rest.

"Since grief and loss cannot be avoided, how can we manage stress to increase our potential for growth and reduce the risk of maladaptation? Encourage the protective benefits of stress and avoid the harmful effects. Right balance of periods of distraction with periods of mindful meditation where we recall our difficulties." (page 100)

Do you know the phrase, "don't tell me how much you know, until I know how much you care"?

Well, by the end of this book I truly believe that Lisa Shulman doesn't only know about how the brain changes after a death, but she cares. “As i walk the line between my own experience of bereavement and my background in neuroscience, I confess my “scientist hat” doesn't’ always fit quite as snugly as usual. Instead, this hat is cocked to one side, leaving room for special moments that defy explanation and bring comfort” pg 101.

In summary, this is another book I'd like to add to my shelf permanently (the copy I read was from the public library). It's a book I'd refer to again and again....and, of course, to tackle that bibliography :)

Sandy It's October, the month of Canadian Thanksgiving, and messages of gratitude are inescapable. I came across an article online that was titled "Go From Grumpy to Grateful in 5 seconds!!" It irritated me. I'm irritated by the simplicity and instantaneous of it. Especially in October, when the bereaved are staring Thanksgiving in the face, wondering about how to navigate this "holiday" of gratitude, togetherness and abundance, when life has been irrevocably changed by something as uncontrollable and in-suppressible as death and grief. Grumpy to grateful in 5 seconds The premise is that changing your language from "I have to" to "I get to" creates more gratitude. For example, changing the statement "I have to go to work today," to "I get to go to work today" does make me feel more grateful for the fact that I have a job I love. I do find that it shifts my perspective in a positive way, and I'm not denying that this could be beneficial. But, with grief, I'm not so sure it's a helpful strategy. Especially in the early days and months after a loss. I think back to the first Thanksgiving after Cam died. I could have said, "I get to go to our family dinner," but the only person I was looking for in that crowded room was him. I could have said, "I got to have him in my life" instead of "I have to live without him," but NO...at that time, the amount of instinctual protest I felt over his death screamed without end "I HAVE TO LIVE WITHOUT HIM IN MY LIFE." Gratefulness felt trite, empty and impossible. In the past, wrote a blog post about this experience, and outlined some ways to make gratitude more accessible while grieving (you can read it here)...but this week, I was reminded by a grieving friend that sometimes, gratitude just isn't there. Period. It got me thinking... This divisive mindset of grumpy or grateful, or sad or happy, sorrow or joy, isn't helpful. It doesn't capture the complexity of human emotion, nor does it promote understanding the parts of ourselves that are so obviously calling out for attention and compassion. What is wrong with feeling grumpy instead of grateful? I think it's an appropriate way to feel if someone you love has just died, and Thanksgiving is approaching. Just because it's October, doesn't mean your grief vanishes and is replaced by gratitude in 5 seconds! If you find yourself unable to feel grateful this Thanksgiving, try releasing the struggle to feel something you don't feel. Don't engage in a discordant battle with yourself. What if you gave yourself permission to just feel what you feel? Invite the sorrow to sit beside you at the table, so it doesn't have to struggle or compete for your attention. When there is no battle inside, you can listen to yourself and your needs with more clarity. What do you really need to feel more peace/balance/support/recognized/acknowledged/heard etcetera? The integration of grief requires authentic expression of your experience. Especially the hard stuff. And, it also requires safe people and places for you to explore your grief and changed self. May your Thanksgiving plans include some of these people and places.... With time, no timeline, and from a place of true integration of your loss(es) and grief, gratefulness may spontaneously arise. And, because you'll have been practiced at paying attention to all aspects of life (the beauty and the pain), it's presence and your awareness of it will be even deeper. I'd love to know your thoughts on this: What is Thanksgiving like for you this year? And, what has gratitude/gratefulness been like in your experience of loss? Wishing you moments of peace this weekend. Namaste, Sandy And a Free Video for You!This summer, I created a poll on instagram to ask you about your experiences with savasana: Do you practice it? What's the easiest part about it? The hardest? Did it change after your loss? I got lots of replies. Here is a summary. Do you practice it? Yes and No. Some practice it regularly. Some did and don't any more. Some don't. The reasons for not include: not having the time (even though you know it helps, it's hard to make the time for it), and being fearful of what will come up during the pose (primarily emotion). For the ones that do, repeated and consistent practice was helpful in releasing chronically held tension. However, even with this knowledge, maintaining a regular practice of savasana was a challenge. What's the easiest? Some reported a feeling of relaxation: "Sinking into the earth," while other reported other things like crying or sleeping. The hardest part? Almost everyone reported the swelling of emotion or the activity in the mind being the hardest part about the pose. Finding the courage to do it was another. A couple of people mentioned the name - Corpse Pose - being disturbing enough that it was a barrier to their practice...and when the name corpse pose was used by a teacher loosely during a class, the practice became triggering, unsettling and unsafe. Did the practice of savasana change after loss? With this question I was hoping to glean information around the effect that grief had on one's ability to relax. For most, it did change after loss - in the ways mentioned above. For some, they had never practiced it before, so post-loss it was a new experience. What have I noticed as a grief-sensitive yoga teacher? In my experience, teaching yoga as a supportive practice for grief, I've noticed how important savasana and relaxation are to living with loss. So important in fact, that I weave the essesnce of savasana into the entire class. The relaxation of effort that one finds in savasana isn't only present in the last 3, 5 or 10 minutes of class, but it is part of the entire experience of yoga asana and mindfulness throughout, especially when it comes to coping with difficult states of mind and emotion. To me, savasana is an orientation to yoga. An emotional stance towards your practice. This pose embodies the nature and purpose of the entire practice. And yet, when I go to "regular" yoga classes, savasana is skimmed over, or worse, skipped completely. If it's not, the guidance is around relaxing the body, with less advice on dealing with mental tension, and usually NO advice on how to deal with emotional release during the pose...which is a very a common experience of those grieving. And so, this important pose - one that embodies the heart of yoga, and is exceptionally helpful to those experiencing ongoing states of suffering - becomes one that is avoided and misunderstood. That is why I created this video. I believe that savasana should be taught and practiced with the same depth of technique as headstand or a fancy arm balancing pose. I believe that the teaching of it should include, not only the body, but information about how to consciously relax the mind, as well as the emotions. And it's not simply "letting go" (a phrase that in its popularity has seemed to lose any real meaning). It's more about becoming deeply aware of your states of mind and emotions, and from there, working wisely with them. So, I hope you enjoy this video. The first 10 minutes are a preamble about why savasana is hard. I recommend you listen to it and take some time to reflect on how our modern and western view of relaxation has shaped your experience and ability to relax. For the practice, you will need a couple of blankets - one rolled up for behind your knees (or a bolster) and one folded for your head (or a small pillow). It may also be nice to have a blanket to cover up with. If you want to explore some of the topics I mention in this video, I have numerous blog posts on the subject: Namaste,

Sandy

I had an exceptionally emotional week last week for a number of reasons, and had an upsurging of raw grief by the end. I was done. Exhausted. Mentally, physicaly and emotionally. I was sleepy in the car and anxious to get home, have a hot shower and crawl into bed. Which I did. But once I was lying down, self talk that resisted rest started to bubble up.

While my legs felt like lead, and they literally sunk into the mattress, my mind started to come up with all-the-things I could be doing - stuff like: dishes, sweeping the floor, this blog post. When my legs didn't respond to that call to action, my mind started getting dramatic: "If you don't get up now, you may never get out of bed again." Has this happened to you? "If I start crying now, I may never stop." "If I rest now, I may never stop." What is this?! Dramatic Sandy was worried I'd lay there forever and never get up again. Wise Sandy piped up with a reality check: "You'll be out of bed in 20 minutes to pee." I had to giggle at this internal dialogue. Myself cutting myself some slack to both rest, and give myself the space to do so. Sure enough, I was out of bed later that night (a couple of times), and I did, in fact, get out of bed the next day. Why do we do this? Why do we mentally resist rest when our bodies so deeply need it? I have a few theories... First, we live in a society that values efficiency and productivity. We hold an unusual status symbol: being busy. It's as though being busy equates with being needed...indespensable...valued...respected by the capitalist machine that makes the world go 'round. We see this in our view of the body as well. The body as a machine. We become practiced at ignoring our instincts to stop - we work when we are sick, we take medicine to get rid of the sore throat and congestion so we can continue on as normal. We adhere to the only-a-few-days-off-after-a-death-rule, returning to work right after the funeral and before the reality of the death has even sunk in. We are always reachable by text, email, messenger or phone, and responses are expected quickly. We push ourselves, without taking care of ourselves. My car gets an oil change more frequently that I take time off work, for goodness sake. Second, this addiction to busyness has become a coping mechanism. If I'm busy, I'm distracted. I don't have time or space to feel. Which, at some times, can be helpful. Other times, not so much. Third, our own personal self-talk and beliefs around rest (which have perhaps been contaminated by points one and two above). I noticed my self-talk/thought while I was lying in bed last week wondering if I'd ever get out. It went something like this: "If I succumb to my fatigue, I've given up." And "my need to rest is proof that things are as bad as they seem, and I can't handle it." Look at the language I've used in the previous statements: succumb, given up, rest means things are bad, I can't handle it. The language I've chosen, highlights my beliefs about rest...interesting. And worrisome. (Be careful how you talk to yourself because you are listening). I'm reminded of the yogic teachings around the constant churning and agitation of thoughts in the mind. The verse in the Yoga Sutras that reads, Yoga citta vritti nirodhah (Chapter 1, v. 2) and means "yoga is the resolution of the agitations of the mind." Judith Hanson Lasater recently described this on the Feathered Pipe Blog. She described the agitations of the mind as being continual and both conscious and unconscious. They are also the root of our lack of understanding about who we really are and what reality is. Noticing my agitated thoughts around rest has got me wondering: How has my culture shaped my beliefs around rest? How do my beliefs about grief and suffering relate to my beliefs about rest? How is resisting rest working for me? How is my identity wrapped up in my ability/inability to rest? What is my reality? (Yoga is the state in which the agitations of consciousness are resolved). I've been following the Nap Ministry on Instagram for a while now. Contrary to the resistance to rest, their slogan is REST AS RESISTANCE. This is from their website: "The Nap Ministry is a meditation on naps as resistance. It is an artistic, historical and spiritual examination on the liberating power of naps. It re imagines why rest is a form of resistance and shines a light on the issue of sleep deprivation as a justice issue. It is counter narrative to the belief that we all are not doing enough and should be doing more. We are community centered. We are focused on radical self-care." YES. These are some of the phrases from Nap Ministry Instagram page that have inspired me to reframe how I view rest:

I know that a very limiting factor with regards to rest and grief is being unable to sleep. Here again, we can broaden our narrow view of rest to include other things.

Rest is a huge part of integrating loss and grief. Grief and rest cannot be "managed" simply by an act of will. It takes surrender. Letting go of the conditions that create more suffering. Letting go of the conditions and agitations of the mind that create rules that simply don't benefit. Letting go of the to dos, and shoulds, simply surrendering to what is truly needed in the moment. So often it's rest. Namaste, ​Sandy Kate Inglis is a Canadian author - not that that really matters, except for the fact that somehow, because we live in the same country, I feel more akin to her. Although, having said that, the more probable reason I feel this way is that she has written a deeply personal book about grief, that resonated with my heart. I don’t think my little book review will do it as much justice as some of the reviews on her website or on Amazon, but I will share what I really liked about it. This memoir is about Kate’s experience when her twin boys were born prematurely. One survived, one did not. Notes for the Everlost is a poetic, raw, and moving account of the trauma and grief of her heart wrenching loss. One of the things I enjoyed the most about this book is Kate’s writing style. She uses creative images, metaphors and explanations to capture aspects of grief that are exceedingly difficult to express with words. She weaves the harsh reality of loss through a layer of lyrical and melodic expression; not in a way that dampens the raw feelings of grief, but in a way that makes it even more powerful. Her words appease the rational and intellectual mind while speaking directly to the abstract and transcendent heart. And, it works. Grief, afterall, is an experience of the heart. This memoir is immensely honest about the depth of pain in grief. Reading it brought back memories of my own grief - and it invoked fear within me. Fear of “it” happening again. Fear of feeling the shock and impossibility of loss again. This, though, was buffered by an undercurrent of hope that ran through the text. Kate has masterfully crafted the book in this way - somehow capturing wholeness in brokenness. As I was reading, I knew that if (no, when) it happens again, I will survive it and cope. Some other aspects of the book that I found really helpful were: The trauma of the healthcare settings: Kate captures the chasm of life saving - in the cold, clinical silos of healthcare - with life ending, and the resultant grief and trauma. I think this is an aspect of healthcare that goes largely unnoticed but is a HUGE dimension of grief - the effects of complicated, complex and emotional medical decisions that people deal with long after they leave the hospital. The misconceptions of grief: Kate dispels the misconceptions of grief the run rampant in our society. She understands how our society mis-handles grief and she writes about her experience in navigating this. She gives practical strategies for dealing with jerks. Perhaps they are well meaning jerks, but, under the pressure of grief, this practical advice is invaluable. She includes the spiritual wrestling and rumbling. The mysterious. The unseen. Loved that. And, lastly, the book ends with a number of pages where Kate writes her reflections year after year. Whereas many grief books only tackle the first year, Kate writes about how her grief was: Integrated Present Absent Healed, and Not healed each year for 10 years! I’ve always struggled with how to understand and explain how “healing grief” feels after so long...and she captures the spiral* of it perfectly. In summary, if you love reading, poetic and detailed images, and memoirs about grief, I'd recommend this book. I think people who have suffered the death of a baby would find it especially resonate, due to the commonality of experience. Having said that though, I thoroughly enjoyed it even though I don't fit that description - I think there is enough universality in the specifics of Kate's story that many people would connect with. Buy Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief here: Maybe this is why we read, and why in moments of darkness we return to books: to find words for what we already know.

*Spiral: A quote by Ashley Davis Bush from the book: Hope and Healing for Transcending Loss

“Grief is like a spiral. You feel like you are going around in circles and coming back to the same material. But in fact, your grief is always in motion. This means that you come back to what seems like old feelings at a slightly different place on the path. You are changing, integrating, grieving, moving deeper, moving higher, always along the turns of this grief spiral. Be patient with yourself in the process.” It was in 1637 that Descartes wrote the phrase je pense, donc je suis, which translates into “I think, therefore I am.” I can’t help but wonder if this is where we went off track. Granted, Rene Descartes was a philosopher so this phrase has more depth than what I'll write about here...but is this where, to quote Robert Frost, two roads diverged in a yellow wood? Where we started to overvalue the mind and cognition and under value the body and emotion? There was another philosopher back then, who took the opposite stance to Descartes. His name was Spinoza. Instead of seeing the mind as a reasoning machine and separate from the body as Descartes did, Spinoza thought the body and mind were one continuous being, where thoughts and feelings are foremost in the body, not the mind. “For his beliefs, Spinoza was vilified and -- for extended periods -- ignored. Descartes, on the other hand, was immortalized as a visionary. His rationalist doctrine shaped the course of modern philosophy and became part of the cultural bedrock” (1). (There is a great NY Times article about this here). Fast forward 382 years and we live in a world where are overly cerebral. We value science, logic, rationality. We need statistics, and evidence. Productivity and objectivity is a marker of success. We are basically floating heads, walking around, detached from our bodies, disconnected from feeling. We are disembodied. Dissociated. I think, therefore I am, is a concept that yogis have been addressing for years. "Yogash chitta vritti nirodhah" meaning: In other words, the true nature and purpose of yoga is to stop the constant chattering, and churning of thoughts in the mind. The yogi channels the power of the mind, the mind does not hold reign over the yogi. The method to do this is multifaceted and robust...and perhaps a topic for a different post. I probably don’t even need to write this obvious fact, but I will: We aren’t just a bunch of heads walking around. Our heads are literally attached to our bodies...(insert cheeky emoji here). In any-case, a more apt phrase worth adopting may be: I feel, therefore I am.

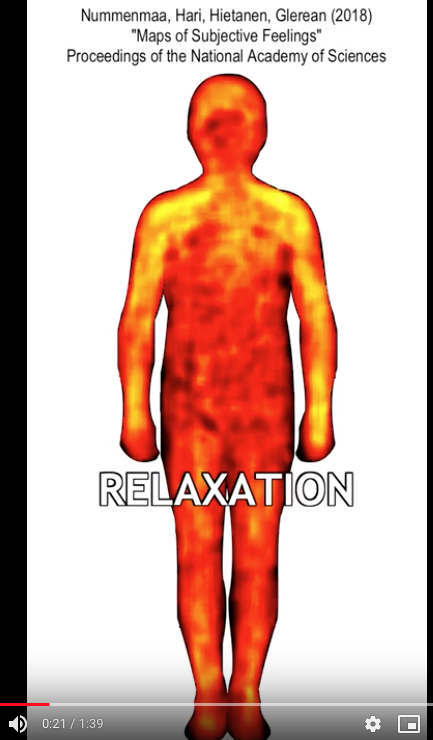

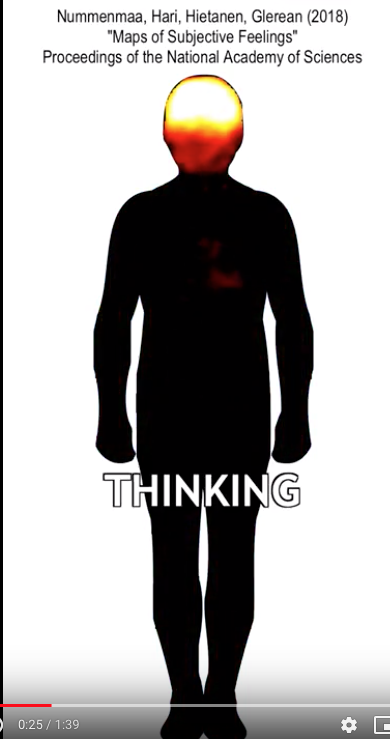

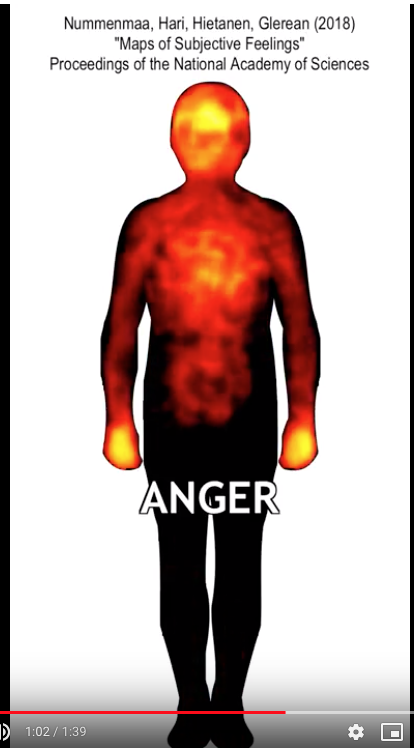

During her experience with cancer she would chant: "I feel, therefore I am." I think grief is similar. For me it was anyway. There was something so visceral and unignorable about how grief showed up in my body. It wasn’t a mountain bike race I could push through...it was complete surrender to a force within myself, and much greater than myself (or my mind, maybe?). Grief forced me into communion with my body. My body and my emotions had more power than my mind...but the hard part was releasing my mind from trying to do it all, and to let my body and emotions guide me. It turns out that Spinoza was right; “Feeling, it turns out, is not the enemy of reason, but, as Spinoza saw it, an indispensable accomplice,” (1) and scientists are just starting to understand it now. In Finland scientists have mapped where more than 1000 participants felt 100 different emotions in their bodies. They compiled the results to create “bodily sensation maps.” What they found was that: “even those feelings you think are all in your head still create sensations in the rest of your body." As co-author Riitta Hari put it, "We have obtained solid evidence that shows the body is involved in all types of cognitive and emotional functions. In other words, the human mind is strongly embodied."” (3) I find it so striking; the areas that light up and the areas that don’t. Our bodies speak to us constantly, through sensation, and lack thereof. We try to think our way through our losses but we can’t. We have the entire rest of our body that is trying to communicate with us... we have to FEEL. Our minds have to understand that we feel. They have to unite. Yoga is one way to do this. The practice unites the body and the mind - to be mutually respectful allies. In Yoga for Grief Support, I teach about the mind - give strategies to tame it...and explore the language of the body. If you want to learn more about the classes and groups I run, you can visit my website by clicking the links below: In person groups in Edmonton Online Program References 1. Emily Eakin, 2003. I Feel, Therefore I am. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/19/books/i-feel-therefore-i-am.html on December 4 2018 2. Krista Tippet,2016. Becoming Wise. Retrieved from: https://onbeing.org/programs/feel-therefore-eve-ensler/ on December 4th 2018 3. Lauri Nummenmaa, Rita Hari, Jari K. Hietanen, and Enrico Glerean, 2018. Maps of Subjective Feelings. Retrieved from: http://www.pnas.org/content/115/37/9198 December 5th 2018 Feel, Feel, Feel...

Sandy This guest post was written by Amy Ebeid On June 23, 2018, I lost my breath. One minute I was driving my two boys (8 and 6) to go see the newest Star Wars movie for their first week of summer vacation…and then a phone call…and then I was gasping for air and sobbing hysterically. My mother was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer on June 23. She had an annoying cough for 6 weeks and some dizziness and then suddenly our lives completely changed. She was 69 at the time of diagnosis. The week before…we had been planning our usual weekends at the beach, discussing the boys’ schedules, gossiping about the news, and ordering matching flip-flops. It disappeared in that moment on June 23. My beautiful, non-smoking, non-drinking, only organic eating mother had over 100 nodules in her lungs and suddenly I also couldn’t breathe. The tightness in my chest and the shortness of breath (obviously massive anxiety) continued as my family fell apart and we began to try and process this diagnosis. I took my children to swim team practice and ignored their swimming as I googled words and phrases like “metastatic”, “pulmonary nodules”, “adenocarcinoma”, and “brain mets” on my phone. I blocked out the laughter at the pool and held my breath as I obsessively looked up every single statistic and research and treatment and prognosis for lung cancer that I could find. I held my breath throughout the day and ordered my eyes to stay dry as I made my boys breakfast while simultaneously texting my mom and my dad and my brother to determine the next doctor appointment, the plan of attack, any new symptoms, and on and on. I went through all the motions of motherhood, while telling my mom that she could beat this disease, and through it all…I couldn’t breathe. My kids would go to sleep at night, my role of mother would end, and the tightness in my chest would explode. I would sob to my husband, to my friends, to my brother, and to my parents. You know this kind of cry. The ugly, hysterical, loud, frantic, unable to breathe cry. I cried as the reality that my life would never ever be the same punched me in the stomach. My husband would rub my back and remind me to breathe mainly because I sounded like I was hyperventilating. And I just didn’t know how. I didn’t know how to breathe in a world where I would lose my mother to lung cancer. See...my mother was my best friend. I called her multiple times during the day, sent her funny memes and articles, watched my children absolutely adore her, planned for her and my dad to visit, and sat by her side on her porch at the oceanfront in Virginia Beach, where they lived. There was no future that didn’t include her. She was my rock. My person. Our matriarch. I knew what a diagnosis of stage 4 lung cancer meant and I couldn’t accept it. I was suffocating at the idea that eventually I would have to figure out who I was without my mother. I held my breath for the first initial weeks. I love running, but whenever I tried to run, by myself or with friends, I still couldn’t breathe and would feel like I was having a panic attack. I knew I needed exercise, so I reluctantly went to my yoga studio during the first week of July. Something quiet felt appealing. Yoga has been a part of my life since 2000. I even went through teacher training, completed my 200 hours, and taught yoga to children. It has always been a quiet form of exercise and an occasional way to calm my worries. On that particular day in July, I hid in the back corner versus my usual front and center spot. And then something amazing slowly began to happen. As my body began to flow with the music through Sun Salutation A and B…I began to breathe. I listened to the instructor’s cues of “inhale” and “exhale” and air suddenly began to move through my body. Tears mixed with my sweat as I began to cry, but I kept breathing. Slow and steady. I placed my hands on my stomach during Savasana and felt the air rise and fall. And suddenly I knew what my own treatment would need to be during my mother’s fight with lung cancer. I needed yoga to help me find my air and learn to breathe again. I went to yoga almost every single day that summer and continued my practice into the fall. During that time, my mother completed brain radiation and began chemotherapy. In September of 2018, she suddenly went into respiratory failure and was subsequently hospitalized. I continued going to yoga when I was home and if I was in the hospital with her…I remembered my practice and found a way to sit with my hands on my stomach and tell myself “Inhale, exhale. Inhale, exhale.” I sat with my mom and held her hand then called my kids and listened to their stories about their day. I went to lunch with my dad and sobbed in the car with him and then face timed my boys and laughed about their new Lego creations. Inhale. Exhale. Inhale. Exhale. I watched my mom’s chest rise and fall with the help of a high flow oxygen machine and matched it with my own breath. Inhale. Exhale. And on and on. We take it for granted. The inhale and exhale of our breath. Breathing helps you stay present. It’s how we relax our minds, lower our stress hormones, and center and ground ourselves. I couldn’t function in those early weeks of June because I forgot to breathe. I either sobbed and gasped for air or I was so desperate to not fall apart that I clamped my lips together and just shut off. My daily yoga practice was the greatest gift I found during my mom’s battle with lung cancer. It helped me survive. It helped me still be me. It helped me still connect to my kids and be their mother. It helped me even smile and laugh with friends occasionally or forget for a brief small second that I was losing the most important person in my life. And on October 23, 2018, I sat with my mom and my family in the hospital room she had been in since September, holding her hand as hard as I could, and as I cried and silently told myself ‘Inhale exhale”…I watched my mom take her last breath. It’s been almost 3 months since I lost my mom. And grief is the hardest, most painful emotion that I have had to learn to carry. It hits in the most unexpected times and I feel gutted all over again. I miss my mom more than I ever imagined I could miss a person. And still every day…I pack my bag and walk into my studio and practice yoga. My instructors know about my loss and I speak to them openly and honestly about my sadness. No pretending or faking. Yoga helps me be present. I move through my heartbreak and loss by helping my body relax and let go of its pain. I let go of my survival mode and allow myself vulnerability and to just be where I am. And at the end of each class, I lie still during Savasana and talk to my mom in my head. Inhale Exhale. Hi mom. I’m finding my way. Inhale Exhale. I miss you so much. Inhale Exhale. You were truly the best. Inhale Exhale. Maybe I will be ok. - Amy

|

AuthorSandy Ayre Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

Classes

|

Helpful Info

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed