|

A memory washed over me today. I remembered a family gathering a few years ago. One of my cousins slid in beside me where I was sitting on the steps of a deck. She was sobbing. "What's happening for you right now?" I asked, a bit surprised by her sudden emotion.

"I just looked over at everyone together and I thought, 'Dad should be here,'" she said. "He should be here and he isn't." Her Dad had died 10 years previous. In our society we tend to focus on the TIME that has passed since someone died, instead of the experiences that have passed. Time is irrelevant when it comes to matters of the heart. It doesn't matter how long it has been. What matters is what your heart has or hasn't had to encounter and feel. There was something in that moment with my cousin - a specific mixture of memory and circumstance that made her miss her Dad. Maybe it was the summer breeze, maybe it was the people who were there, or the reminiscing of old times that was happening. Whatever it was, that moment made her encounter her loss in a new and unexpected way. I remember my Dad at that same family gathering alive and sort-of well. I remember seeing him socializing and laughing with his oxygen tank in a backpack on his back. My Dad died in November 2019. I missed our big family Christmas party that year, and then Covid hit. I'm anticipating the next family gathering will bring up raw and new grief because I haven't had to navigate that familiar group of people without him yet. The isolation and physical/social distancing that we've all been facing due to Covid has insulated us against many of the social encounters and functions that would normally and understandably cause a natural wave of grief. We've become "out of practice" of encountering grief in this way. It's not only large family parties. It's little things. It's Sunday family dinners. Going to our family cabin and spending a weekend there. Favorite restaurants, and enjoyed activities. It's seeing my parent's friend group together, and my mom on her own. It's even more that I'm not expecting to be sure. What is it for you? What hasn't happened yet that you anticipate will be hard? Here are a few tips for navigating re-opening while grieving...

0 Comments

"Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world's grief. The events in our world right now (climate change and losses due to fires and floods, the Covid pandemic and the uprising against discrimination and oppression) have brought grief, loss and trauma to the forefront of our collective experience, albeit in different ways. I feel like we are all the care-givers of a grieving world. And it is SO HEAVY. With all this going on, I’ve been wondering: How can I care for the people who need it? How will we cope with ALL of this? What can I do? I feel frantic to do something - get on zoom, get on Facebook or Instagram live, plan something to help...on and on and on...and simultaneously I think, "I don't know what to do." This tension between the two states is what this post is about. The quote that I opened this newsletter with has been a guiding one for me: "Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world's grief. Do justly now, love mercy now, walk humbly now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.” I will not abandon the work that needs to be done in the realm of grief support. And yet, another guiding mantra I have is,“You are helpful in your helplessness.” At first glance, it can seem impossible to balance these two things: Helplessness, but not abandoning the grief I witness. I believe, however, that these two states are not incompatible with each other. Rather, there is a creative tension between them. They need each other. Especially now. In this context, being helpless doesn’t mean doing nothing. It means understanding that there is nothing that you can do to fix or take away someone’s pain. Recognizing helplessness creates connection and support because the griever is less alone when there is someone else willing to sit in the darkness with them. This, actually, is really hard for us helpers. Sometimes, the more we explore someone’s pain with them, the harder it is to remain "helpless." I see this in myself at times in my personal and professional life, when I’m witnessing someone else's grief or uncertainty. I want to jump in to make it all better. I want to take away the pain. I want to spew solutions, and tell them “everything is going to be OK.” {In moments like this, when you notice yourself placating, as yourself, "What am I trying to make more comfortable?" So often it's OUR OWN discomfort we are trying to appease, not the person we are supporting.} Although this protective reaction is well meaning, it's not helpful. I have to mentally stop myself. I remind myself that there is absolutely nothing that I can say that will take the person’s pain away. Simply listening, and upholding the experience of the other person is the most genuine, compassionate and helpful response. Listen to their story, listen to their hurt. Listen to their fears. Don't try to change it for them. Stay humble. Henri Nouwen captures this so vividly in this quote: “Healing means, first of all, the creation of an empty but friendly space where those who suffer can tell their story to someone who can listen with real attention. As healers we have to receive the story of our fellow human beings with a compassionate heart, a heart that does not judge or condemn but recognizes how the stranger’s story connects with our own. We have to offer safe boundaries within which the often painful past can be revealed and the search for a new life can find a start. Our most important question as healers is not, what to say or to do? But, how to develop enough inner space where the story can be received? Healing is the humble but also very demanding task of creating and offering a friendly empty space where strangers can reflect on their pain and suffering without fear, and find the confidence that makes them look for new ways right in the center of their confusion.” As a grief care-giver, you create the conditions for the griever to find their own way through their pain. This is how, as the quote says, "you are not obligated to complete the work." Everyone has to integrate their own loss themselves... Still, we cannot abandon grief, grievers, or ourselves. In our society, how we deal with grief is a social justice issues. Perhaps it is more accurate to say how we don’t deal with grief is a social justice issue. We must commit to contributing to social change and justice for the grieving and the bereaved. We must remain open to witness and receive the discomfort within ourselves, and in our societies. We must do the personal work we need to be able to be in genuine connection and compassionate presence with others. We cannot abandon grief. If we can support grief we can empower grievers, and with empowerment, people can integrate their losses in meaningful ways. We can be helpful in our helplessness. November was a rough month in my world. On November 14th, after a two year illness, my Dad died. He had pulmonary fibrosis. Over the past two years, I have been mentally drafting a blog post called: When It Happens Again. IT being death and emotional trauma. I remember feeling such protest as I was considering the fact that IT could (would) happen again. A deep revolt and fear around knowing what grief is like, and not wanting to go down that path again. This mental blog post I had drafted was going to be a piece around how I would cope with grief the next time 'round, based on everything I had experience and learnt since the first time 'round. Things like:

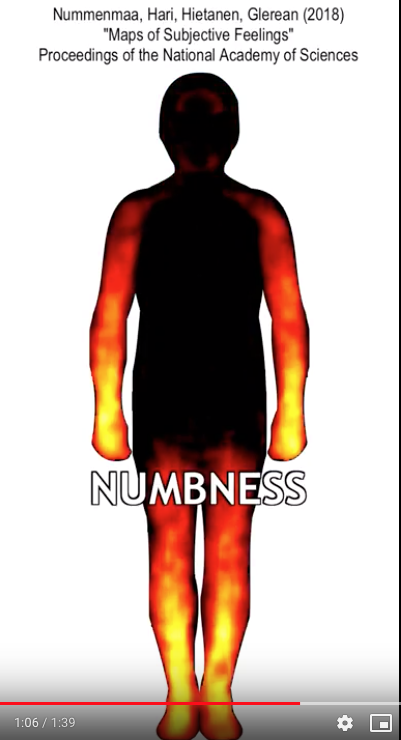

I never did write that post. I kind of wish that I had - then I could refer back to it as a little pep talk for myself. Now that IT has happened, all the best laid plans I had mentally made, have dissolved into the cocoon of shock. I'm steeped with numbness and shock that has dulled the realities of my outer and inner world. My mind isn't working as quickly. I'm forgetful. I start 16 different tasks in a day and don't complete any of them. I didn't brush my hair or my teeth today and I have nothing to show for how busy I felt. I don't feel the protest the way I thought I would. That must have burned itself out during my dad's illness as I watched him slowly (and then quickly) decline. My anxiety is gone. I was paralyzed before his death about what was going to happen. Now it's happened and I've been relieved of that worry. That lack feels numb too. And yet, the world says speed up when everything within my body and mind says slow down. I feel this tug of war in my gut and my chest and I dread having to navigate it; It takes so much extra energy. I know the numbness and shock serves a purpose. The heart can't feel the full reality of the loss at once. It is not worth forcing myself out of this cocooned place. My wise body/mind/spirit will naturally dose itself with the pain and the reality of the loss, in it's own time. My conscious mind may not be privy to this timeline. So, what do I do? I start right where I am. I rest. I cocoon. Be gentle with myself. I've noticed more intrusive thoughts in the past few days around the circumstances of his death. This too, I know is normal. Instinctual even. There is a natural tendency to go over it all, again and again. Cognitively trying to make sense of it. While *the world* wants me to get on with living, and get back to life, I know that pausing, even going backwards into the past is important grief work. It makes the unreal real, and is an important part of processing the reality of the death. I've found myself gently approaching the pain and reality a couple of nights ago. I drove by the hospital and looked up to the window that was his room. It made my chest ache. I want to live-backwards. I want to spend some time reviewing what-the-hell-just-happened. I'll probably write it out. Get those thoughts out of my head and onto paper. I may even walk from where I would park my car, to the unit he was on, just to remember and feel it when I'm ready to. But, who knows! Grief is unpredictable, and living-in-the-moment for me at this time means responding to whatever need arises, when it does. It's all vital work. Grief work. Mourning work. I do know that this time 'round I am part of (and can rely on) a community of people who "get it" to support me and I feel all those people in my cocoon with me.

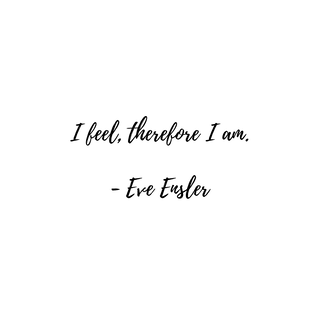

This time 'round, I'm more open to receiving care and being cared for. That feels really nice. Thank you. To those near and far, known to me and unknown. The grief warriors that live this every day. We are not alone. Sandy It's October, the month of Canadian Thanksgiving, and messages of gratitude are inescapable. I came across an article online that was titled "Go From Grumpy to Grateful in 5 seconds!!" It irritated me. I'm irritated by the simplicity and instantaneous of it. Especially in October, when the bereaved are staring Thanksgiving in the face, wondering about how to navigate this "holiday" of gratitude, togetherness and abundance, when life has been irrevocably changed by something as uncontrollable and in-suppressible as death and grief. Grumpy to grateful in 5 seconds The premise is that changing your language from "I have to" to "I get to" creates more gratitude. For example, changing the statement "I have to go to work today," to "I get to go to work today" does make me feel more grateful for the fact that I have a job I love. I do find that it shifts my perspective in a positive way, and I'm not denying that this could be beneficial. But, with grief, I'm not so sure it's a helpful strategy. Especially in the early days and months after a loss. I think back to the first Thanksgiving after Cam died. I could have said, "I get to go to our family dinner," but the only person I was looking for in that crowded room was him. I could have said, "I got to have him in my life" instead of "I have to live without him," but NO...at that time, the amount of instinctual protest I felt over his death screamed without end "I HAVE TO LIVE WITHOUT HIM IN MY LIFE." Gratefulness felt trite, empty and impossible. In the past, wrote a blog post about this experience, and outlined some ways to make gratitude more accessible while grieving (you can read it here)...but this week, I was reminded by a grieving friend that sometimes, gratitude just isn't there. Period. It got me thinking... This divisive mindset of grumpy or grateful, or sad or happy, sorrow or joy, isn't helpful. It doesn't capture the complexity of human emotion, nor does it promote understanding the parts of ourselves that are so obviously calling out for attention and compassion. What is wrong with feeling grumpy instead of grateful? I think it's an appropriate way to feel if someone you love has just died, and Thanksgiving is approaching. Just because it's October, doesn't mean your grief vanishes and is replaced by gratitude in 5 seconds! If you find yourself unable to feel grateful this Thanksgiving, try releasing the struggle to feel something you don't feel. Don't engage in a discordant battle with yourself. What if you gave yourself permission to just feel what you feel? Invite the sorrow to sit beside you at the table, so it doesn't have to struggle or compete for your attention. When there is no battle inside, you can listen to yourself and your needs with more clarity. What do you really need to feel more peace/balance/support/recognized/acknowledged/heard etcetera? The integration of grief requires authentic expression of your experience. Especially the hard stuff. And, it also requires safe people and places for you to explore your grief and changed self. May your Thanksgiving plans include some of these people and places.... With time, no timeline, and from a place of true integration of your loss(es) and grief, gratefulness may spontaneously arise. And, because you'll have been practiced at paying attention to all aspects of life (the beauty and the pain), it's presence and your awareness of it will be even deeper. I'd love to know your thoughts on this: What is Thanksgiving like for you this year? And, what has gratitude/gratefulness been like in your experience of loss? Wishing you moments of peace this weekend. Namaste, Sandy It was in 1637 that Descartes wrote the phrase je pense, donc je suis, which translates into “I think, therefore I am.” I can’t help but wonder if this is where we went off track. Granted, Rene Descartes was a philosopher so this phrase has more depth than what I'll write about here...but is this where, to quote Robert Frost, two roads diverged in a yellow wood? Where we started to overvalue the mind and cognition and under value the body and emotion? There was another philosopher back then, who took the opposite stance to Descartes. His name was Spinoza. Instead of seeing the mind as a reasoning machine and separate from the body as Descartes did, Spinoza thought the body and mind were one continuous being, where thoughts and feelings are foremost in the body, not the mind. “For his beliefs, Spinoza was vilified and -- for extended periods -- ignored. Descartes, on the other hand, was immortalized as a visionary. His rationalist doctrine shaped the course of modern philosophy and became part of the cultural bedrock” (1). (There is a great NY Times article about this here). Fast forward 382 years and we live in a world where are overly cerebral. We value science, logic, rationality. We need statistics, and evidence. Productivity and objectivity is a marker of success. We are basically floating heads, walking around, detached from our bodies, disconnected from feeling. We are disembodied. Dissociated. I think, therefore I am, is a concept that yogis have been addressing for years. "Yogash chitta vritti nirodhah" meaning: In other words, the true nature and purpose of yoga is to stop the constant chattering, and churning of thoughts in the mind. The yogi channels the power of the mind, the mind does not hold reign over the yogi. The method to do this is multifaceted and robust...and perhaps a topic for a different post. I probably don’t even need to write this obvious fact, but I will: We aren’t just a bunch of heads walking around. Our heads are literally attached to our bodies...(insert cheeky emoji here). In any-case, a more apt phrase worth adopting may be: I feel, therefore I am.

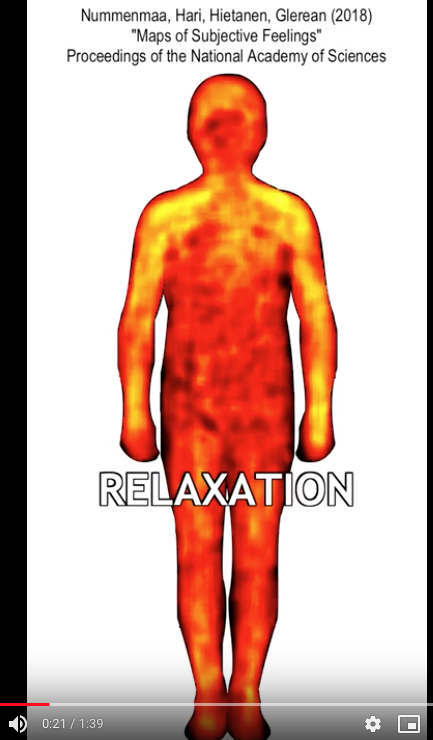

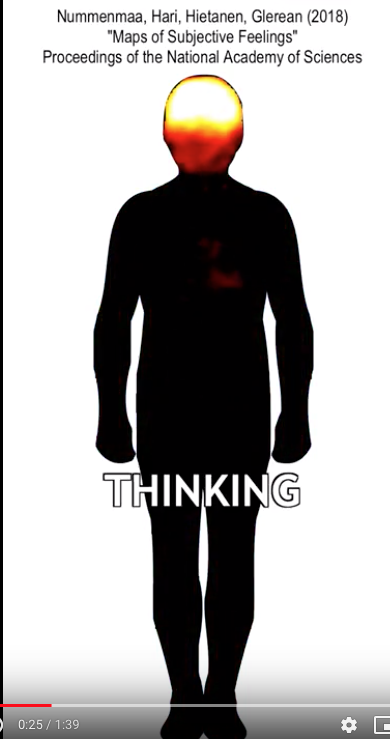

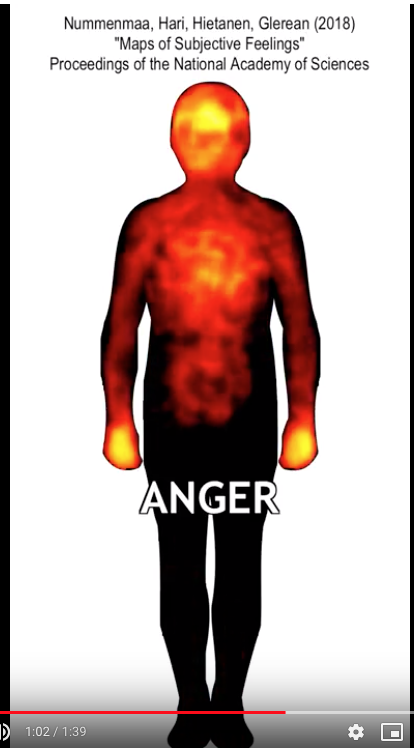

During her experience with cancer she would chant: "I feel, therefore I am." I think grief is similar. For me it was anyway. There was something so visceral and unignorable about how grief showed up in my body. It wasn’t a mountain bike race I could push through...it was complete surrender to a force within myself, and much greater than myself (or my mind, maybe?). Grief forced me into communion with my body. My body and my emotions had more power than my mind...but the hard part was releasing my mind from trying to do it all, and to let my body and emotions guide me. It turns out that Spinoza was right; “Feeling, it turns out, is not the enemy of reason, but, as Spinoza saw it, an indispensable accomplice,” (1) and scientists are just starting to understand it now. In Finland scientists have mapped where more than 1000 participants felt 100 different emotions in their bodies. They compiled the results to create “bodily sensation maps.” What they found was that: “even those feelings you think are all in your head still create sensations in the rest of your body." As co-author Riitta Hari put it, "We have obtained solid evidence that shows the body is involved in all types of cognitive and emotional functions. In other words, the human mind is strongly embodied."” (3) I find it so striking; the areas that light up and the areas that don’t. Our bodies speak to us constantly, through sensation, and lack thereof. We try to think our way through our losses but we can’t. We have the entire rest of our body that is trying to communicate with us... we have to FEEL. Our minds have to understand that we feel. They have to unite. Yoga is one way to do this. The practice unites the body and the mind - to be mutually respectful allies. In Yoga for Grief Support, I teach about the mind - give strategies to tame it...and explore the language of the body. If you want to learn more about the classes and groups I run, you can visit my website by clicking the links below: In person groups in Edmonton Online Program References 1. Emily Eakin, 2003. I Feel, Therefore I am. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/19/books/i-feel-therefore-i-am.html on December 4 2018 2. Krista Tippet,2016. Becoming Wise. Retrieved from: https://onbeing.org/programs/feel-therefore-eve-ensler/ on December 4th 2018 3. Lauri Nummenmaa, Rita Hari, Jari K. Hietanen, and Enrico Glerean, 2018. Maps of Subjective Feelings. Retrieved from: http://www.pnas.org/content/115/37/9198 December 5th 2018 Feel, Feel, Feel...

Sandy This guest post was written by Amy Ebeid On June 23, 2018, I lost my breath. One minute I was driving my two boys (8 and 6) to go see the newest Star Wars movie for their first week of summer vacation…and then a phone call…and then I was gasping for air and sobbing hysterically. My mother was diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer on June 23. She had an annoying cough for 6 weeks and some dizziness and then suddenly our lives completely changed. She was 69 at the time of diagnosis. The week before…we had been planning our usual weekends at the beach, discussing the boys’ schedules, gossiping about the news, and ordering matching flip-flops. It disappeared in that moment on June 23. My beautiful, non-smoking, non-drinking, only organic eating mother had over 100 nodules in her lungs and suddenly I also couldn’t breathe. The tightness in my chest and the shortness of breath (obviously massive anxiety) continued as my family fell apart and we began to try and process this diagnosis. I took my children to swim team practice and ignored their swimming as I googled words and phrases like “metastatic”, “pulmonary nodules”, “adenocarcinoma”, and “brain mets” on my phone. I blocked out the laughter at the pool and held my breath as I obsessively looked up every single statistic and research and treatment and prognosis for lung cancer that I could find. I held my breath throughout the day and ordered my eyes to stay dry as I made my boys breakfast while simultaneously texting my mom and my dad and my brother to determine the next doctor appointment, the plan of attack, any new symptoms, and on and on. I went through all the motions of motherhood, while telling my mom that she could beat this disease, and through it all…I couldn’t breathe. My kids would go to sleep at night, my role of mother would end, and the tightness in my chest would explode. I would sob to my husband, to my friends, to my brother, and to my parents. You know this kind of cry. The ugly, hysterical, loud, frantic, unable to breathe cry. I cried as the reality that my life would never ever be the same punched me in the stomach. My husband would rub my back and remind me to breathe mainly because I sounded like I was hyperventilating. And I just didn’t know how. I didn’t know how to breathe in a world where I would lose my mother to lung cancer. See...my mother was my best friend. I called her multiple times during the day, sent her funny memes and articles, watched my children absolutely adore her, planned for her and my dad to visit, and sat by her side on her porch at the oceanfront in Virginia Beach, where they lived. There was no future that didn’t include her. She was my rock. My person. Our matriarch. I knew what a diagnosis of stage 4 lung cancer meant and I couldn’t accept it. I was suffocating at the idea that eventually I would have to figure out who I was without my mother. I held my breath for the first initial weeks. I love running, but whenever I tried to run, by myself or with friends, I still couldn’t breathe and would feel like I was having a panic attack. I knew I needed exercise, so I reluctantly went to my yoga studio during the first week of July. Something quiet felt appealing. Yoga has been a part of my life since 2000. I even went through teacher training, completed my 200 hours, and taught yoga to children. It has always been a quiet form of exercise and an occasional way to calm my worries. On that particular day in July, I hid in the back corner versus my usual front and center spot. And then something amazing slowly began to happen. As my body began to flow with the music through Sun Salutation A and B…I began to breathe. I listened to the instructor’s cues of “inhale” and “exhale” and air suddenly began to move through my body. Tears mixed with my sweat as I began to cry, but I kept breathing. Slow and steady. I placed my hands on my stomach during Savasana and felt the air rise and fall. And suddenly I knew what my own treatment would need to be during my mother’s fight with lung cancer. I needed yoga to help me find my air and learn to breathe again. I went to yoga almost every single day that summer and continued my practice into the fall. During that time, my mother completed brain radiation and began chemotherapy. In September of 2018, she suddenly went into respiratory failure and was subsequently hospitalized. I continued going to yoga when I was home and if I was in the hospital with her…I remembered my practice and found a way to sit with my hands on my stomach and tell myself “Inhale, exhale. Inhale, exhale.” I sat with my mom and held her hand then called my kids and listened to their stories about their day. I went to lunch with my dad and sobbed in the car with him and then face timed my boys and laughed about their new Lego creations. Inhale. Exhale. Inhale. Exhale. I watched my mom’s chest rise and fall with the help of a high flow oxygen machine and matched it with my own breath. Inhale. Exhale. And on and on. We take it for granted. The inhale and exhale of our breath. Breathing helps you stay present. It’s how we relax our minds, lower our stress hormones, and center and ground ourselves. I couldn’t function in those early weeks of June because I forgot to breathe. I either sobbed and gasped for air or I was so desperate to not fall apart that I clamped my lips together and just shut off. My daily yoga practice was the greatest gift I found during my mom’s battle with lung cancer. It helped me survive. It helped me still be me. It helped me still connect to my kids and be their mother. It helped me even smile and laugh with friends occasionally or forget for a brief small second that I was losing the most important person in my life. And on October 23, 2018, I sat with my mom and my family in the hospital room she had been in since September, holding her hand as hard as I could, and as I cried and silently told myself ‘Inhale exhale”…I watched my mom take her last breath. It’s been almost 3 months since I lost my mom. And grief is the hardest, most painful emotion that I have had to learn to carry. It hits in the most unexpected times and I feel gutted all over again. I miss my mom more than I ever imagined I could miss a person. And still every day…I pack my bag and walk into my studio and practice yoga. My instructors know about my loss and I speak to them openly and honestly about my sadness. No pretending or faking. Yoga helps me be present. I move through my heartbreak and loss by helping my body relax and let go of its pain. I let go of my survival mode and allow myself vulnerability and to just be where I am. And at the end of each class, I lie still during Savasana and talk to my mom in my head. Inhale Exhale. Hi mom. I’m finding my way. Inhale Exhale. I miss you so much. Inhale Exhale. You were truly the best. Inhale Exhale. Maybe I will be ok. - Amy

I am frequently asked about what yoga studios and classes are good. I find this a difficult question to answer because there are so many variables at play. Especially after the death of a loved one. There are as many styles of yoga as there are teachers. Not only is each class a different intensity level, but also each teacher adds their own unique flare, communicating their own personal interpretation of how yoga has been felt or expressed their bodies, to the class. I encourage students to find a teacher that they like. One that they “buy into.” Who’s teaching resonates. I believe there has to be a sliver of common ground, where the life experience, and the experience of yoga as the teacher has interpreted it, meets the student’s. This helps to make a yoga practice feel possible – this is something I can do - and fosters a sense of trust and safety. From this place, a teacher will challenge his/her students, but the pre-requisite for all good learning, and in this case, good mourning, is safety. *** In my past life, I was a competitive mountain bike racer. Living in Edmonton, my off-season (winter) was months long. So, I took up yoga. I practiced physically challenging styles of yoga – Ashtanga and vinyasa – because I wanted to improve my physical conditioning by strengthening and stretching. These classes “met me where I was at.” They met my physical needs and my mental expectations about what I wanted my yoga to be. After Cam died, I continued with this intense style of yoga. In the first few months it helped to balance me – I was anxious, restless and confused. It took the edge off. Still in shock, my old routine was comforting. It was something my body was good at and could do. It was something I had control of, as every other area of my life spun out of control. As the shock wore off and I realized anew that Cam died, grief punched me in the stomach and left me on my knees. As the reality of my situation set in, I became increasingly fatigued. I didn’t have the physical energy to get out of bed, never mind a 90-minute power yoga class. I was emotional and labile. I’d burst into tears mid pose, and spend all of savasana fighting back sobs. I wasn’t buying into, or comforted by the teachings the various teachers provided. They felt cliché: I wanted to scream, “Everything doesn’t happen for a reason,” and “Fuck positive affirmations!” None of it felt applicable to my life, and in fact, it made me feel shameful for not measuring up to par. I felt out of place. I didn’t feel safe. Those classes were no longer a good fit for me. I found an exceedingly gentle yoga class taught by a woman, Beth, the basement of her house. For two hours every Wednesday, we would gather. In those two hours, we would do three poses, using cushions, blocks and bolsters for support and comfort. We spent oodles of time breathing, and learning meditation. These classes were challenging in a different way. They met me where I was at - terrified, confused and raw. The slow gentle postures allowed me to feel my body, and my emotions, which was possible because I felt safe there – as safe as I could feel with raw grief coursing through my veins. In any case, I wasn’t the only once crying in Beth’s class. *** If you live in a major city, the breadth and choice of yoga classes can be over-whelming. If you’ve never done yoga before, I would suggest starting gentle, so you can learn the basics, and have an affirming experience. From there, find a teacher that you like. Try a few until you find a good fit. Everyone’s grief experience is so individual, and everyone comes to yoga a various points in their life. If you remember to find a class to “meet you where you’re at,” you’ll find something that reflects your needs in the moment. Remember, it’s OK to experiment and change your mind…life isn’t constant: sometimes you’ll need the intensity; sometimes you’ll need the quiet. The choice is yours and the options are out there. A good companion for grief is the book “Understanding Your Grief” by Alan Wolfelt. Although it's not a yoga book, much of Wolfelt's philosophy is very yogic, and I found it a helpful resource to blend what I was learning about grief in my life, into my yoga practice. For this book, and more recommendations, check out my bookstore. Namaste, Sandy

I recently started reading a book called Full Body Presence by Suzanne Scurlock-Durana. The first chapter had me hooked.

In those first few pages she wrote of something that I have known on some level, but seeing it in print made it so much more tangible. She describes many instances when we don't trust our internal awareness - for example, feeling intense grief over a dear friend moving away but being told by people around you that your grief was not important, and shameful..."Why are you worried about it? You have many other friends, right?" Or having a creepy reaction to someone in your life and being told to stop being so silly and jumping to conclusions. "In all these examples, your body was telling you something important, but those around you tried to convince you that what you were sensing wasn't real or valid" (page 9). It was this lack of trust of our inner and deepest self that struck a chord within me. She further describes how a lack of trust of our inner worlds leads us to looking for external sources to shape, define, solve, remedy our lives. Take grief for example. Our grief slows us down physically and mentally. We feel tired, lethargic, numb, confused, disorientated, lost and sometimes even crazy. Our emotions are all over the map. We feel so different, our lives feel foreign. We wish we could go back in time and never let go of the past. The worst part is this: In the throngs of grief you don't know what to do. You've never lived like this before. If you don't know, and don't trust what you feel inside, you look outside yourself for the answers. You look to a society that pushes speed, rewards efficient solutions, reveres stoicism, and demands productivity. We, as a society, don't do well with stillness, solitude, loneliness, pain, and hurt. So here we are. "Keep really busy," they advise. "Don't cry. She wouldn't want you to be sad," they scold. "You need to get back to how you were before he died," they push. "Don't live in the past," they warn. "Stop feeling sorry for yourself," they say. "Quit playing the victim." Need I go on? We are taught to not trust our grief. Intuiting the message, reading between the lines, understanding the subtext, we hear this: "Whatever grief-striken energy you feel inside you is wrong. You feel the wrong things. You think the wrong things. You are doing it wrong." How horrible. What I teach in Yoga for Grief Support is this: "Whatever grief-stricken energy you feel inside you is something to pay attention to. There is wisdom there. Let's learn, together, how to touch those wounds with compassion." If you feel it, it's real. If you feel it, it's important. If you feel it, you can heal it. Be curious about it. What is it saying? What is it's message? What is it's deepest need? What if you believed that your internal world is telling you something very important about how you need to heal and nurture your broken heart? Imagine, just for a second that the grief within you can be trusted - even in it's painful. I mean, you are hurt, afterall. Let's spend some time there. Say to it, "I will take care of you." This is what moving towards your pain is. You must move (gently and with no rewards for speed) towards (and through) your pain to heal. Suzanne Scurlock-Durana writes that our bodies are "incredible navigational systems that inform us constantly, from our gut instincts to our heart's deepest yearnings" (page 5). Yeessss! Let's shift our relationship to our instincts and our senses from one of mistrust and doubt to reliance, and connection. Together. I'd love to hear your feedback on this book if/as you read it. Please feel free to post comments under this blog. Namaste, Sandy  Something very important is happening. Anyone who ever has lost someone, or who will lose someone has to know. That's everyone. That's me, and you and someone you know. There are changes coming to the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). Which, to make a long story short, will make it easier for people who are grieving to be diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder. Basically, if you are experiencing symptoms such as sadness, altered sleep patterns and changes in appetite, for longer than two weeks (2 WEEKS?!) after the death of a loved one, you meet the criteria for depression. 2 weeks? Are we human? Or are we robots?

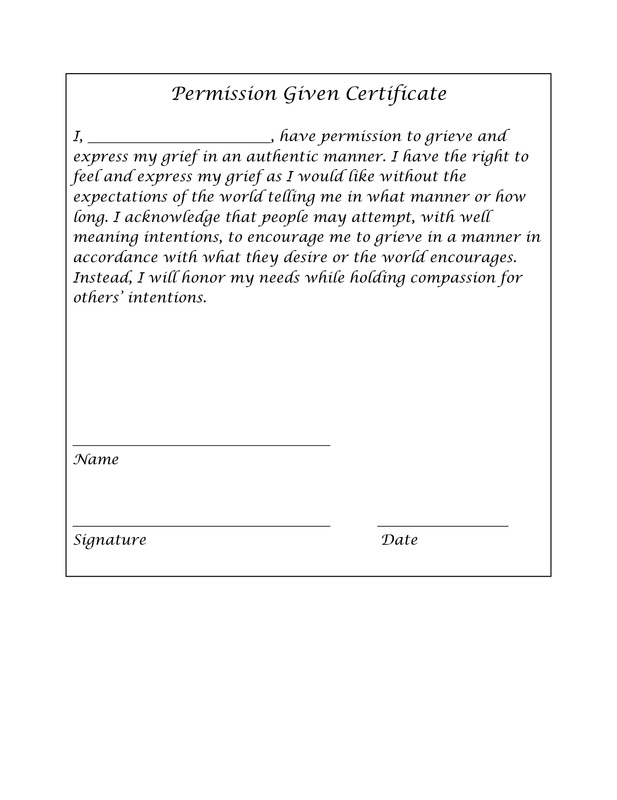

I recognize that the above description is over-simplified. I recognize that in some cases, people who are grieving can, and are, diagnosed with depression and prescribed medication. I also HOPE with every fiber of my being that the decision to do so is made by a clinician who has a firm grounding and understanding in what it means as a human being to experience and live through loss as a natural and normal part of life, and NOT a pathology that can be SOLVED by medication. In some cases I'm sure medication can help, but to have a 2 week limit on a human experience like grief is scary and irresponsible, in my humble opinion. Six months after Cam's sudden and tragic death a medical professional asked me if I had a good Christmas. No. I didn't. It was horrible. It was excruciating. It was hell for me and for his family. Christmas wasn't a celebration that year. Nor the next. Nor the one after that, if the truth be known. Next comment made (without further conversation or acknowledgment of my reality): "You sound depressed, you need medication." Actually, what I needed was someone to acknowledge that feeling sad after the death of my loved one was normal. That feeling a loss of joy and lightness is a natural response to devastation. That the symptoms of grief are a wise and organic response to the fact that I had something that I loved be taken from me. That not feeling like celebrating Christmas 6 months after his death was completely congruent with my life experience and that what I needed was people to sit with me there in darkness, not fix the unfixable. Heart to heart, another human being should understand that grief is painful, messy and life changing. AND, that it is OK...more than OK, it's part of healing a grieving heart. A hug would have been nice as well. Ted Gup has this to say, in an article written in the NY Times called Diagnosis: Human "I fear that being human is itself fast becoming a condition. It’s as if we are trying to contain grief, and the absolute pain of a loss like mine. We have become increasingly disassociated and estranged from the patterns of life and death, uncomfortable with the messiness of our own humanity, aging and, ultimately, mortality. Challenge and hardship have become pathologized and monetized. Instead of enhancing our coping skills, we undermine them and seek shortcuts where there are none, eroding the resilience upon which each of us, at some point in our lives, must rely. Diagnosing grief as a part of depression runs the very real risk of delegitimizing that which is most human — the bonds of our love and attachment to one another. The new entry in the D.S.M. cannot tame grief by giving it a name or a subsection, nor render it less frightening or more manageable. The D.S.M. would do well to recognize that a broken heart is not a medical condition, and that medication is ill-suited to repair some tears. Time does not heal all wounds, closure is a fiction, and so too is the notion that God never asks of us more than we can bear. Enduring the unbearable is sometimes exactly what life asks of us. But there is a sweetness even to the intensity of this pain I feel. It is the thing that holds me still to my son. And yes, there is a balm even in the pain. I shall let it go when it is time, without reference to the D.S.M., and without the aid of a pill." Well said Ted. I feel SO passionate about being a voice speaking out for and standing up for being human. For compassion, understanding, and vulnerability in all our hurts, griefs and frailty. As Mother Teresa said, "I have found the paradox that if you love until it hurts, there can be no more hurt, only more love." Let's love, people. Of course, this is only MY opinion. I invite you to listen to a podcast done by the BBC called Medicalising Grief. It is only available for 4 more days, so please listen soon. It is a well done, and well rounded look at the issues around the changes coming to the DSM-V and what it mean to stakeholders (drug companies...yes, interesting indeed), clinicians, you and me. If you love someone. If you've lost someone. If you will lose someone - please listen. Knowledge is power. Inform yourself now, so when the inevitable happens you can direct your own care and be informed about who you let into your grief to help you make decisions about your care. With love, Sandy When I was asked to write this guest blog, I was honored and am still very honored. As a dance/movement therapist, I was excited to share from this perspective and advocate for the body's role in grief, mourning, and healing and then I let myself become caught up in expectations about having to write from this perspective. I thought I had to write the most poetic piece but through that journey the topic of this blog blossomed: permission. A topic that may seem so benign on the outside but in reality is important. Sometimes it is the journey that we find what is already naturally onside of us. To live authentically and in the continued interest of self disclosure, my intention is to not write the perfect post but rather speak from the heart and an embodied place in support of my own journey and your journey. The world may place many expectations on how we move through grief and bereavement. People may attempt to push someone to move on or present ideas meant to be helpful with well meaning intentions. Action is being advocated for and as a consequence a place to explore and move through one's own process is not given the space and freedom to develop. Everyone has their own way of expressing and journeying through their grief. We may feel it in our hearts, our stomachs, or our limbs. We may express our feelings through stillness, spoken words, written words, art, music, or dance. There is wisdom is what messages the body conveys about our grief and how we choose to convey our inner process. Trusting one's own process can be freeing. Our grief and healing process is our own and it is okay to go through one's own journey! Yes, I am saying that everyone has permission to be as you are in your process.I hereby give all of you permission to grieve, mourn, move, heal, and be who you are in your own process. Below I have included a blank form that you may find useful. Peace be with all of you. Kimberlee Bow, MA, R-DMT Kimberlee Bow obtained her Master’s in Somatic Counseling Psychology with a concentration in Dance/Movement Therapy. She obtained her R-DMT or Registered Dance/ Movement Therapist credentials by meeting the high standards that are required of the field. Dance/Movement Therapy is based on empirically supported evidence that the body, mind, and spirit are interconnected. A dance/movement therapist therefore uses movement in a psychotherapeutic manner to encourage emotional, cognitive, psychical, and social integration and growth. Dance/Movement Therapy is suited for individuals, groups, family, and couples and can be used with multiple different populations in many mental health or medical health settings. For more information please visit the American Dance Therapy Website. There, one can find more information about Dance/Movement Therapy, the organization, great resources, and access to a list of Dance/Movement Therapists in your area.

Kimberlee Bow works in Colorado in a private practice with children and families. Additionally, she brings Dance/Movement Therapy to elder groups, veterans, at-risk youth, support groups, intergenerational groups, and continues to expand her work. Her website, www.kimberleebow.com, is currently under construction, but will up soon. For more information please email Kimberlee and she will be happy to answer questions. |

AuthorSandy Ayre Categories

All

Archives

December 2022

|

Classes

|

Helpful Info

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed